How Did Europena Explorers Adapt to Environments Wile Traveling

2. Indians and Europeans on the Northwest Coast: Historical Context

The history of the tardily 18th and early 19th centuries in the Pacific Northwest is in many ways a story of convergence. It is the story of two groups of people—ane European and one Indian—converging on the land that nosotros now call dwelling. Each group possessed its own social and political structures, economies, and ways of interacting with the natural environment. In addition, each group had its own means of thinking about and representing the events that took place. The convergence of dissimilar groups, and of different ways of doing and thinking almost things, created a diverse customs of people who found ways to alive together in a new and altered globe. This story of convergence took place over many decades, and information technology continues into the present.

This bundle of materials, all the same, focuses on the period between 1774 and 1812, the commencement years of contact betwixt Native and European peoples. The twelvemonth 1774 marked the first of documented contact betwixt Europeans and Indians on the Northwest Coast, and the year 1812 marked the starting time of a new stage of development, when overland fur traders took center stage. It was during this brief but pivotal flow that Indians and Europeans met and developed a trading relationship that laid the groundwork for time to come social, political, and economic interactions. This was the era when ships from Espana, England, America, French republic, Russia and Portugal visited the Northwest Coast and first met the Nuu-chah-nulth, Makah, Salish, Kwakwaka'wakw, and Haida peoples.

This introductory essay is divided into iii parts: Imagining, Coming together, and Living Together. The Imagining section provides a glimpse of the ways in which some Europeans and Indians imagined each other before they actually met. The Meeting portion describes some of the cultural baggage that each grouping brought to their encounters. Essentially, this section explains why Europeans came to the Pacific Northwest in the first place, and why Indians chose to merchandise and socialize with Europeans. Because the meeting of these cultures was both enabled and express by geography, this section besides describes some of the unlike means in which each group responded to the natural environment. Finally, the Living Together segment gives examples of the means in which each culture learned about the other. It focuses on economic and political aspects of the procedure of learning to live together. Sometimes this learning took the form of peaceful adaptation, and sometimes it took more violent forms. Yet by the start of the 19th century, each group had a much more realistic sense of the other than they had possessed a mere 30 years earlier.

In some respects, the story of cultural contact in the Northwest resembles that of Christopher Columbus's famous voyages to the New World starting time in 1492. Simply by the time Europeans came to the Northwest nearly 300 years had passed, and European explorers had traveled to and mapped near all parts of North and South America—except the Pacific Northwest. Hither in the Northwest, the story of contact and convergence began around the time of the American Revolution, when American colonists had settled no farther westward than the Ohio River valley. While some American colonists certainly cherished dreams of westward expansion, no one yet dreamed of a nation that stretched from sea to sea.

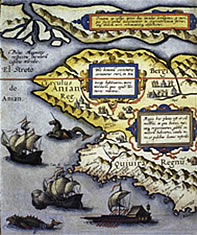

As the movement for independence took concord along the eastern seaboard of what is now the United States, the ancient people of the Pacific Northwest went about their business undisturbed. They had little or no cognition of what was going on in Europe or its American colonies, just as Europeans and American colonists had little or no cognition that the Pacific Northwest fifty-fifty existed—it was a gaping hole in their maps of the world (encounter document 2 and document 3). All the same, for many European explorers, entrepreneurs, and heads of country, this bare space on the map held infinite hope. Wealth, fame, and run a risk beckoned from that unknown geographic infinite, and their lure was compounded by fable.

Imagining

The fable of the Northwest Passage particularly enthralled Europeans. This passage, sometimes referred to as the Strait of Anian, was a waterway that supposedly continued the Pacific Body of water to the Atlantic. Such a waterway would have greatly facilitated trade and communication between Europe and east asia because travel between these locations mandated choosing among three unattractive options. One had to undertake either an arduous overland journeying along the Silk Road, or a long and hazardous ocean voyage westward around either the tip of South America or eastward effectually Africa and across the Indian Ocean. Thus in the 18th century European traders cherished the promise of finding an hands accessible waterway across North America. They based their hopes on legendary accounts well-nigh the Northwest Passage.

One of the most mysterious and influential of these accounts was that of Juan de Fuca (document one). In 1596 an elderly Greek pilot by the name of Apostolos Valerianus (a.k.a. Juan de Fuca) confided a strange and wonderful tale to Michael Lok, the British administrator at Aleppo, Syria. Lok subsequently submitted the story for publication. De Fuca claimed that in 1592 he had been a member of a Spanish bounding main voyage forth the Pacific Coast north of United mexican states. The expedition had sailed to about 47 degrees northward latitude, at which point de Fuca's boat had turned eastward into a strait that seemed to cut deep into the North American continent. De Fuca said that the expedition had sailed for twenty days in the strait and come out in the Atlantic Sea, at which betoken it retraced its road to United mexican states. De Fuca claimed that the natives living nearly the strait were rich in gilded, silver, and pearls.

Of course, the Strait of Juan de Fuca does not cross the North American continent, and the Native people of the Northwest were never in possession of large quantities of gilt, silverish, or pearls. Yet, like the legend of El Dorado, the fabled Northwest Passage caught the imagination of many Europeans and persisted in the minds of explorers. In 1786 Englishman Charles Barkley discovered the entrance to a big strait at approximately the latitude de Fuca described, and he named the Strait of Juan de Fuca after its 16th-century promoter.

Just as Europeans were dislocated well-nigh the geography and natural resources of the country they were and then eager to explore, Indians were initially confused by the ships and people who met them on the Pacific coast. While conducting inquiry among the Clatsop people during the belatedly 19th century, ethnographer Franz Boas heard a story about the Clatsops first contact with Europeans (document 7). The storyteller claimed that an one-time adult female was walking forth the Oregon coast one mean solar day and saw the first European ship to visit the area. Considering she had never seen a ship earlier, she conceived of the strange object as a monster that looked like a whale with two trees sticking out of it. A creature resembling a bear with a human confront came out of the monster. She then went domicile to tell her strange tale. Many Clatsop people came to the body of water to see the foreign matter she described, and they met the bear-similar Europeans on the beach. The Europeans wanted water, and in the confusion ane Clatsop human being went aboard the ship, while his relatives fix burn to information technology. The Clatsops were apparently able to save much of the copper and iron from the ship, as they became rich by trading these goods with their neighbors inland and along the coast. The riches and celebrity that the Clatsops gained in their encounter with a European send could accept served every bit incentive for other Indian peoples to greet and trade with ships that came to their homes. In this style, the promise of riches encouraged both Europeans and Indians to trade with each other.

Coming together

In the 1770s, when sustained contact between Europeans and Indians in the Pacific Northwest began, European explorers, traders, entrepreneurs, and national governments were playing a catchy game of international chess. Europeans came to the Northwest intending to claim territory, make a profit, win intellectual glory, catechumen souls, and maintain peace with their neighbors—all at the same time. The game that they played had certain rules, the most central of which was the right of commencement discovery and possession. The way in which these 2 words were divers, however, led to much confusion and diplomatic hedging by all parties.

For case, shortly subsequently Columbus arrived in the New World in 1492, the papacy drew up a document known as the Treaty of Tordesillas. The treaty asserted that Spain had a right to merits all lands due west of a sure point in the Atlantic Ocean—basically, most of the unexplored continents of North and South America. At that time, the Pope was a major power broker amid the Christian European nations, and he therefore negotiated this treaty not between Spain and the people of the New World, but between Espana and Portugal, the 2 most avid colonial powers of the 15th century. Partially equally a consequence of this agreement, Spain became the wealthiest country in Europe in the 16th century considering of the golden and argent extracted from its colonies in present-day Mexico and Republic of peru. Because they were decorated administering their enormous empire in Southward America and Central America, Spanish leaders did not deem it necessary to immediately inhabit, or fifty-fifty explore, all the territory allotted to them in the Treaty of Tordesillas. Nearly 300 years later on, the Castilian presence in the Pacific Northwest was withal negligible. The Spanish were additionally secure in their claim to lands on the Pacific Sea due to Balboa'south 1513 trek across the Isthmus of Panama. Upon sighting the blue waters of the Pacific, Balboa claimed the ocean for Spain. Of grade, the Chinook and Makah and Salish and other peoples of the Pacific Northwest in no mode considered themselves Spanish subjects, nor did they even know that Spain had laid claim to their country.

The Russians did know about the pretensions of Castilian land claims in the New World, only they had no intention of letting those claims go unchallenged. Backed past Catherine the Groovy, a Russian expedition led by Vitus Bering set off from St. Petersburg in 1725 and marched toward the Pacific Coast. Sent in part to establish whether or not Asia and Due north America were really separate continents, this expedition discovered the Bering Strait in 1728. The explorers then sailed toward Alaska but never landed. Nonetheless, the trek laid the groundwork for the fur trade with China. Vitus Bering and his successors soon did establishing trading posts at various points along the declension of what is at present Alaska. This activity alarmed the Castilian, who had hoped that the Northwest Declension would lie undisturbed past European powers until the Spanish Empire had the time and resources to colonize it. It was in this climate of suspicion that the Spanish launched the Perez Expedition of 1774 from the naval base at San Blas, Mexico, to the Northwest Declension.

Perez and his men were sent to spy on Russian traders, just they were also specifically instructed to have possession of the state as far as 60 degrees due north latitude. For the Spanish, taking possession of the land entailed erecting a large wooden cross onshore and burying a glass bottle at its foot, containing written documentation of Espana's claim. Adverse weather prevented Perez from taking these actions, merely his expedition did see with the people of the Northwest at two locations (document 4 and document 5). Commencement, he met the Haida people of the Queen Charlotte Islands (now a part of British Columbia). After spreading feathers on the water near Perez's gunkhole, the Haida proceeded to trade with Perez'south crew. The Haida offered sea otter skins, hats, blankets, and other items made from cedar trees in commutation for metallic appurtenances from Perez'southward boat. This boat-to-gunkhole merchandise was repeated about a calendar month afterward with some unidentified people (probably the Nuu-chah-nulth) off the coast of Vancouver Isle.

Although Perez and his men forged tentative economical bonds with the people of the Northwest Coast, they failed to meet their political objective, which had been to accept effective possession of the state in the face of other imperial competitors. In add-on to facing competition from the Russians, the Spanish also had to contend with the English, who did non acknowledge the validity of the Treaty of Tordesillas and who were busy looking for lands that seemed outside the realm of actual Spanish control. The Spanish believed that the all-time style to continue competitors out of their territory was to keep their maps, sea logs, and explorations secret from other European powers. Since the Spanish did not publish records of their explorations, the only way to testify their claims was to leave some sign on the country. Unsatisfied with the results of the Perez trek, the Spanish sent the Bodega-Hezeta expedition of 1775 to make landfall and found Spanish claims to the Pacific Northwest with more authorization. This expedition did reach state and found crosses, fulfilling the Spanish authorities'south goals.

The Spanish had good reason to be nervous about the encroachments of other European powers. In improver to the Russians, who were expanding their Alaska-based fur trade south, western European nations—such as France, the netherlands, and particularly Great Britain—were becoming stronger colonial powers and threatening Kingdom of spain's leading role in the colonization of the New World. In 1745, and more extensively in 1774, the British Parliament promised to handsomely reward the person who discovered a Northwest Passage across North America—a passage widely believed to exist smack in the heart of the state claimed past the Spanish throne.

While Europeans fretted and schemed, the Indian people of the Pacific Northwest were concerned with their own affairs. The people of the Northwest coast lived in orderly, hierarchical societies based on extended family unit groups. Several of these groups might exist on particularly friendly terms because of intermarriage, for example, and be centrolineal against other groups. Southern peoples (those most and beneath the 49th parallel) particularly feared encroachment past their powerful neighbors to the north (specially the Haida). Disharmonize between various groups occasionally broke out, but these conflicts were not especially encarmine by European standards.

Because these Native societies were quite hierarchical, leading families sought to maintain and advance their social positions past accumulating and and then distributing material wealth. In addition, accumulation of wealth and displays of ability and prestige often prevented encroachment by neighboring groups. Overall, trading for services and material goods was a vital component of Indian life on the Northwest Coast. When Europeans arrived with trade goods, coastal Indians saw the opportunity for advancement within their ain societies by accumulating rare and exotic European goods such as copper, beads and iron blades. In return the Europeans sought furs, and it became relatively simple for powerful Native leaders to have command of the conquering, preparation, and trade of furs within a given area. Leaders such as Main Maquinna of Nootka Sound and Chief Wickeninish of Clayoquot Audio exercised control over trading empires in the interior, organizing labor and setting the terms for trade at the coast. As their wealth grew, and so did their prestige, considering they were able to redistribute more and more appurtenances.

For most coastal people of the Pacific Northwest, wealth was acquired and distributed through the potlatch system (document 8).Under this system, extended families would vie for prestige in the community by accumulating vast amounts of merchandise goods and then giving them away in ceremonies called potlatches. Potlatches were held to commemorate special occasions of importance to the host family. They were generally ceremonial celebrations involving hundreds of people and often lasting upwardly to two weeks. Guests at the potlatch would witness and, by their presence, attest to the importance of the host family and the commemorated consequence. In return, the host family would requite away, its accumulated wealth—the more appurtenances it gave away, the college its social prestige rose. In this manner, wealth was redistributed throughout the community. European goods were perfect for potlatching, and they therefore became quickly integrated into the local economies.

Like the Europeans, the Native people of the Northwest Declension were participants in a materialist, acquisitive, and wealthy economy. Past the late 18th century, the commutation of prestige goods (mainly non-food items) amidst the coastal peoples of the Pacific Northwest was all-encompassing and competitive. For most coastal groups, material wealth and social status were closely linked. The Europeans who came to the Northwest Declension in the late 18th century understood this acquisitiveness because it had parallels in their own economic organisation. Thus, the exchange of appurtenances over the side of boats made sense to all involved. Simply here the similarities between the two economical structures ended.

For most Europeans and Americans of the 18th century, wealth was acquired and distributed in a global capitalist economic system. This economic system was non exactly like the one we know today, where most governments perceive costless trade every bit positive. In the 18th century, global commercialism mostly functioned effectually the principles of mercantilism, an economic philosophy that held the amount of wealth in the world to be finite. Because there was causeless to be only a sure amount of wealth to be shared by all, nations competed confronting each other for the largest portion of that wealth. Wealth was often based in natural resource, then nations sought to claim large tracts of state all over the earth. Trade was by and large tightly controlled by national governments, and trade protection in the class of tariffs, embargoes, and privateering (a polite term for piracy) was the social club of the day.

Mercantilist ideas besides helped produce a organisation of colonialism. European nations like Spain, England, France, and Portugal sought to increase their wealth by establishing colonies in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Some of these colonies were settlement colonies, and some were for merchandise alone, but all revolved around the central thought of increasing the wealth of the mother land past generating portable raw materials. (Colonies also increased the wealth of mother countries by providing markets for European goods, a function that became increasingly important during the 19th century.) Female parent countries ofttimes imposed trade restrictions on their colonies, and so that their inhabitants could simply trade with representatives of the female parent country. Naturally, the black marketplace was rather big, as were the number of means to circumvent merchandise restrictions.

Mercantilist capitalism and colonialism fueled European nations' interest in the Americas, and the want to accumulate prestige appurtenances drove littoral Indians to merchandise with the Europeans. In this fashion, the common ground of trading brought the ii people together.

However, when European travelers traded for furs—and for fish and fresh vegetables to relieve illnesses like scurvy that plagued sailing crews—they unwittingly exposed Indian populations to European diseases like influenza and smallpox. At that place are various theories about how smallpox was introduced to the Northwest Coast, but well-nigh historians agree that this deadly disease commencement began to ravage Indian populations in the region betwixt the mid-1770s and early 1780s. Because Native peoples had never before been introduced to the disease, they had no natural immunity, and a virgin-soil epidemic ensued. In combination with other diseases such as influenza and malaria, smallpox wiped out roughly 65 to 95% of Northwestern Indian populations by 1840. Though there is a swell bargain of dispute about precontact Native populations, it seems off-white to say that the Indian population of the Pacific Northwest (including present-day Alaska, British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon) cruel from over 500,000 in 1750 to somewhere around 100,000 by 1850. By way of comparing, the 14th-century Blackness Plague in Europe and Asia claimed the lives of ane-third of the population there. Smallpox and other diseases did kill some Europeans in the Pacific Northwest, just not nigh at the same charge per unit equally the illnesses decimated Native populations. In add-on, the Europeans who died were replaced by a growing stream of travelers and traders from Europe and the The states.

Merely as the surroundings affected Europeans and Indians differently at a biological level, these groups

also responded to their surroundings in dissimilar ways. Indian groups on the coast made all-encompassing use of cedar trees and salmon, for example. Cedar bawl, with its long, malleable fibers, was perfect for weaving baskets, hats, and clothes. Cedar was also used for constructing housing, canoes, and boxes. For

littoral peoples, as well every bit their neighbors in the interior, salmon provided a nutrient staple and functioned in a formalism capacity as well. Indian people also actively shaped their environment, often using fire to articulate the state and brand it more than favorable for hunting and gathering food.

For many Indian people of the Northwest, the natural environment was animate. That is to say, the animals and specific locations on the country were live with meaning and formed the center of an oral literature common to the people of a specific language group. Stories nearly Coyote, Raven, Eagle, and Beaver are expert examples of these types of oral literature (certificate 10). Though Europeans certainly had some literature describing animate landscapes (the Grimm Brothers' fairy tales, for case), they approached the Pacific Northwest in a unlike fashion.

The 18th-century intellectual and cultural motility chosen the Enlightenment shaped the perspectives and values of many European explorers. Philosophers, scientists, and politicians imagined the world as a giant laboratory in which everything worked according to rational, scientific principles. In this logical world, all ills could be cured by the accumulation of knowledge and the awarding of logic. One of the goals that Enlightenment thinkers ready for themselves was the attainment of complete knowledge of the natural world. To this finish, European nations sent botanists, astronomers, cartographers, linguists, and other scientists to the far corners of the world to collect noesis and to heighten the prestige of their respective states. To these men, the Pacific Northwest was a wilderness to be explored, catalogued, and named (document nineteen and document 21). Unlike most Northwest Declension Indian peoples, for whom the land and animals were active participants in daily life, Enlightenment-era scientists viewed the natural world equally an object for study. The English, French, Spanish, and Americans all sent scientific exploring expeditions to the Pacific Northwest during the tardily 18th and early 19th centuries. Additionally, many military expeditions too carried scientists aboard.

The giant tract of unmapped land in the Pacific Northwest appears to have been similar a siren song for these scientific explorers—not simply would they accept the opportunity to discover new plants, animals, languages, climates, and ways of life, but they also harbored hopes of discovering riches also. These men made detailed maps of the area, noting good anchorages where trade might exist facilitated, likewise as fertile cropland and the location of arable game (document 22 and document 23). Their sponsoring governments made use of this information to choose which lands were most valuable and which could be negotiated away to the other European powers. No European power wanted to give abroad the Northwest Passage inadvertently, simply because no thorough survey of the country had been made. Therefore, although the pure accumulation of knowledge was their stated goal, scientists as well served political ends.

Scientists were not the but Europeans interested in the environment and geography of the Northwest, however. European traders and travelers of all kinds observed and remarked upon the vast forests, the waters thick with marine life, and above all, the weather (certificate 17). Visitors to the Northwest oft described their environment in terms of commodities—forests were wood lots where masts for ships could be procured, animals were skins that could be traded in China for tea and silk. Almost all visitors wrote about the Northwest as a wilderness, fifty-fifty though they sometimes stressed its park-like qualities. They did not perceive the ways in which Native peoples managed and shaped the landscape, instead imagining that the Northwest was a wilderness untouched past man intervention.

Living Together

The Indian people of the Northwest Coast and the European travelers to this region both came from materially avaricious, trade-oriented cultures, and they chop-chop discovered this common ground. The language of merchandise was easily comprehensible to all parties, and formed the basis for the earliest relationships between Indian and non-Indian people in the Northwest. Beginning with the Perez Expedition of 1774, trade goods were exchanged over the sides of boats, apparently to the mutual satisfaction of all parties. It seems that for Indians and Europeans akin, the goods that were exchanged were initially curiosities—interesting, decorative, and occasionally useful items, simply zilch that drastically changed the lives of parties on either side of the exchange. This blazon of relatively disinterested merchandise lasted less than a decade.

Captain James Cook'southward 1778 visit to the Northwest Coast marked a turning point in the economic and social history of the region. Melt was on a mission of exploration for the English language authorities, and he stopped at Nootka Sound to go fresh water and merchandise for food. He and his men met the Nuu-chah-nulth people who lived around the sound, and the two sides engaged in trade. As part of these exchanges, Cook's men took aboard several bounding main otter pelts.Cook'south sailors did non perceive the pelts to have any cracking value, and they used them for bedding on the voyage to China. At the port of Canton, however, it presently became clear that stylish Chinese women coveted the furs; merchants offered to pay outrageous prices for the suddenly stylish pelts. Cook's men fabricated a small fortune and nearly mutinied over their desire to return to Nootka Audio to pick upwardly more furs. Discussion of the value of sea otter pelts spread amidst traders, and by 1785 James Hanna had made a fortune trading atomic number 26 bars for furs in Nootka Sound and so selling the furs in Macao. Other merchants followed in his wake, and the Northwest Declension soon became inundated with traders of many nationalities.

Faced with and then many traders seeking to buy their sea otter pelts, the Indian people of the Northwest Coast responded shrewdly. As the demand for furs increased, the prices set past Indian traders skyrocketed in the years after Cook's initial voyage. Just as the influx of gold, argent, and other goods from the New Globe had transformed the European economy in the 16th century, Native economies in the Pacific Northwest were transformed by contact with European colonialism and capitalism.

At first, the region'south Native peoples used European imports within the context of their own economies, saving upward trade goods for later potlatches, and bartering for fe tools and ornaments that had preexisting purposes in their societies (document 13 and document 17). But over the course of a few decades, the economies of coastal peoples began to center around the production of furs for consign. For instance, the Indian people who handed the furs over the sides of European boats were not the same people who went hunting for sea otters, or even the same people who prepared the pelts for trade. Yet because these coastal traders were the first to receive compensation for the furs, they began to organize the product of furs and to compete with other traders for the resource of the hunters and pelt-curers. This reorientation toward the export of raw materials laid the groundwork for future extractive industries that would come to narrate the economy of the Pacific Northwest.

The sea otter trade restructured Native economies, simply information technology impacted whites' economical practices as well. European and American traders had to change their methods to comply with Native norms, because Indians set the terms of the fur trade—both in terms of method and toll (equally the skyrocketing price of furs indicated). European traders wanted to come to the coast, rapidly take on a full cargo of furs, and depart only as quickly to China, where they could substitution the precious furs for a cargo of silk, tea, and spices before returning to Europe or America. The Indian peoples of the Northwest Coast preferred to trade in the context of an elaborate and more than slow-moving establishment of social relations. They ofttimes refused to trade substantial quantities of furs unless the European merchants came ashore to their villages, where a commemoration of eating, drinking, dancing, and singing ensued. These ceremonies sometimes stretched on over weeks and months, and many European traders were forced to spend the winter on the coast in order to collect enough furs to fill their cargo holds. Indian fur traders too speedily learned that Spanish, English, American, and Dutch merchants competed with i some other. Indian traders played these groups off one another, encouraging competition until they had obtained the highest possible price for their furs.

As Europeans and Indians lived together in Nootka Sound and elsewhere in the Northwest, their political activities and hierarchies became intertwined. The infamous Nootka Controversy demonstrated the extent to which Europeans and Indians had become invested in each other's lives. In late 1789, British, American, and Castilian vessels met in Nootka Audio—much to the frustration of the Spanish, who claimed sole possession of the Northwest Declension. The deportment of Estéban José Martínez, commander of the Spanish fort at Nootka (certificate 15), precipitated the crunch. Under orders to proceed British or Russian interlopers out of Nootka Sound, Martínez seized an English send under the command of Captain James Douglas. Douglas protested and argued that considering his ship was funded by Portuguese interests, it was therefore nominally Portuguese. He also claimed (falsely) that he had simply sought refuge in Nootka Sound to repair his transport. Subsequently spending a week under arrest, he was allowed to leave the sound.

These events disturbed Maquinna, Wickeninish, and other ancient leaders who were allies of the English. Sighting other English language vessels approaching Nootka Sound, Chief Maquinna sent out canoes to warn the budgeted traders that problem was afoot with the Castilian. The warnings fell on deaf ears, and the hotheaded James Colnett sailed his ship directly into the sound. Neither Martínez nor Colnett possessed the diplomatic skills to negotiate a solution to the ensuing confrontation. Colnett'southward ship was undeniably English, and Martínez's orders clearly stated that he was to detain all English language vessels on the coast. Both men flew into a rage, insulting and threatening one another, and Martínez arrested Colnett and his coiffure. Some English sailors were allowed to go ashore, and these men complained to Maquinna that the Spanish had no right to preclude the British from trading at Nootka. One of Maquinna'due south relatives, Principal Callicum, loudly protested confronting Martínez's deportment and asked him to release the captives. Martínez responded by firing a gun at Callicum. Although he missed, i of his crew did not. Callicum vicious dead in front of his married woman, child, and dozens of European and Native witnesses. Maquinna and his followers responded past withdrawing inland and refusing further contact with the Europeans for many months.

Once news of Colnett's and Martínez'due south actions reached Europe, Kingdom of spain and England stood poised for war over Nootka Sound and the Northwest Declension. The Castilian claimed the right of first possession, based on the Bodega-Hezeta Expedition's building of crosses in 1775. The English, citing Spain's tardy publication of these claims, claimed the correct of first possession based on buildings synthetic onshore by John Meares in 1789 (certificate thirteen). Ultimately, the effect was decided by military strength. England had a strong navy and then did its ally, Kingdom of the netherlands. Only when the Spanish turned to their traditional marry, French republic, they were disappointed. The French Revolution was in full swing, and Louis Sixteen could not aid the Spanish. French revolutionaries, inspired by the rhetoric of the American Revolution, were in no mood to assist the Spanish monarch defend his colonial claims. By 1790 it became clear that Kingdom of spain had to take chances a naval disharmonize, which it had almost no hope of winning, or take a diplomatic settlement dictated by the English. This settlement, known equally the Nootka Convention, stated that Spain was to turn over to England all lands bought and occupied by Meares. After the location of these lands had been determined, a line would be drawn between lands that were in the sole possession of the Castilian and lands that were open to both nations.

In order to enforce the settlement decided by the Nootka Convention in 1790, representatives of England and Spain met at Nootka Sound in 1792. To investigate and constitute their claims in the Pacific Northwest, the Spanish sent Don Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra, and the English language dispatched Captain George Vancouver. Dissimilar Martínez and Colnett, Vancouver and Bodega y Quadra were patient and level-headed men (document 16 and document 24). Nonetheless, the two men had difficulty reaching an agreement since the terms of the 1790 Nootka Convention were cryptic, partly because so much of the region's geography remained unknown. In add-on, Vancouver and Bodega y Quadra heard alien reports almost recent events from Nuu-chah-nulth and American traders who had been eyewitnesses. For example, Maquinna denied selling whatever land to Meares at all. Furthermore, Bodega y Quadra wanted to institute a articulate boundary between Castilian and English language claims, but Vancouver thought the Nootka Convention did not grant him the ability to negotiate permanent borders (document 24 and document 25). Only instead of arguing, these men spent their time dining on each other's ships and beingness entertained in Nuu-chah-nulth villages. They reestablished cordial relations with Chief Maquinna, who returned to his habitation on Nootka Sound after he was bodacious that Martínez was no longer in command there. The two captains too agreed to explore the region farther and to share their geographic knowledge with each other.

Their explorations filled in many of the blank spaces on Europeans' maps (certificate 22 and document 23). Bodega y Quadra and his political party circumnavigated Vancouver Isle, proving that it was not part of the mainland—every bit many previous explorers had thought. Vancouver'south coiffure charted the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the interior waterways continued to information technology. His trek demonstrated that the strait led to the Puget Sound, not to some mythical Northwest Passage. Because Vancouver and Bodega y Quadra shared data, both parties learned that Puget Audio could be a fantastic harbor for large ships. Information technology became apparent that Nootka Sound was not the only good port north of San Francisco and that Nootka's strategic significance had been overrated. Bodega y Quadra after turned the Castilian fort at Nootka over to the English. He moved his men south to Neah Bay to establish a fort signifying the northernmost border of Spain'southward possessions. (Although this fort lasted but a few months, information technology was the starting time European settlement in the area that would become the State of Washington.) Fifty-fifty though Bodega y Quadra and Vancouver did not resolve the Nootka Controversy themselves, they established the friendly relations and acquired the geographic knowledge that made a final settlement possible.

Later the Nootka Controversy concluded, Nootka Sound gradually became less and less important to explorers, diplomats, and traders from Europe and the United States. Spanish and English negotiators ended their disagreement past signing the Second Nootka Convention in 1794. This agreement granted the Spanish sovereignty over the coastline south of Neah Bay. Areas to the north, including Nootka Sound, remained free ports where ships from all nations could land. Substantial numbers of European and American traders continued to visit Nootka until 1803, when violence erupted forth the audio. The crew of the American send Boston killed several Nuu-chah-nulth people, and its captain repeatedly insulted Chief Maquinna. The chief and his followers responded by boarding the Boston and killing its crew, sparing merely 2 men, John Thompson and John Jewitt. Thompson and Jewitt lived as Maquinna'southward captives until 1806, when another American ship negotiated their release (document 27 and certificate 28). The attack on the Boston made merchants extremely wary of landing at Nootka. Though trading did resume subsequently Maquinna released Thompson and Jewitt, the trade was never again equally vigorous as it had been in the late 18th century. Nootka Sound was once the most important place in the known Northwest, but today information technology is far removed from the economic centers of the region, and it is accessible only by boat or aeroplane.

Conclusion

Afterwards the Nootka Controversy, the main area of contact between Indians and Europeans moved to the s, centering on the mouth of the Columbia River. In 1792 American Captain Robert Grey became the first non-Indian to navigate and map the Columbia River. Afterward Gray publicized his findings, many American traders began visiting the region effectually the Columbia. Fifty-fifty though English captains had initiated the maritime fur trade in the Northwest, the English became distracted by their military struggle with French republic later on Napoleon'south ascension to power during the late 1790s. Although the Spanish remained an occasional presence on the Northwest Coast, they, besides, were distracted past domestic affairs and only dabbled in the fur trade. Thus, American traders came to dominate the maritime fur merchandise between 1795 and 1814. Americans concentrated on trading and more often than not stayed out of the political struggles among European nations. Both the Spanish and the English were willing to overlook Americans' presence in the Northwest, and the Americans capitalized on this fail. In fact, they were so successful in the trade—and Northwest Coast Indians were such skilled hunters—that the sea otter was about extinct in the region by the commencement decade of the 19th century.

The maritime fur trade was only a short chapter in the history of the Northwest, and it gradually became supplanted by the state-based fur merchandise. Inspired by the overland voyages of Alexander MacKenzie, who became the get-go person to cross North America by country in 1793, and Lewis and Clark, who reached the oral cavity of the Columbia in 1805, overland fur traders began to look with interest at the Pacific Northwest. Fur-bearing land mammals, such as beavers and bears, were arable in this region. During the first and second decades of the 19th century, the Canadian-based N West Visitor became the area'southward most powerful fur trading enterprise by establishing a network of trading posts throughout the interior of the Northwest. Seeking a foothold in the fur merchandise, John Jacob Astor, an American entrepreneur, established a trading company headquartered in what is now Astoria, Oregon. Established in 1811, the company functioned for but a brusk fourth dimension because Astor sold out to the North Due west Company after the War of 1812. Though Astor's functioning was short-lived, the overland merchandise in furs was just beginning. In 1821 the North Due west Company merged with its rival, the Hudson'southward Bay Visitor, and the resulting combination dominated the economic system of the Northwest for the next 25 years.

Every bit the overland fur merchandise replaced the maritime merchandise, the nature of the relations between Native and European peoples began to modify somewhat. Not surprisingly, Indians and whites had learned from their early on experiences with each other forth the Northwest Coast, and their later relationships built on those forged in the early years of contact. Although episodes of violence periodically strained these relationships, the overland fur trade continued the more often than not peaceful patterns of interaction established during the maritime fur trade. However, the advent of land-based trading ensured that Europeans and Americans were no longer mere visitors who bought furs and shortly returned home: land-based traders often lived in the Northwest for decades at a time. The permanence of their presence brought new twists to the relationships established with Native peoples. Many traders married Native women, and the children of these unions—known as the métis—often became fur traders themselves. Native peoples, Europeans, Americans, and the métis formed new and hybrid means of trading and living together. These means of living together persisted until the late 1840s, when the establishment of the Oregon Trail and the arrival of American settlers shattered the globe made by the fur trade and opened a new chapter in the history of the Northwest.

| Main | Section Three | Section IV | Section V | Department VI |

0 Response to "How Did Europena Explorers Adapt to Environments Wile Traveling"

Post a Comment